PART I—The Two Ways You “Mass Balance” in Market-based Transportation Emissions Accounting and Reporting

This is Part I of a two-part series exploring a “market-based” accounting and reporting approach to transportation decarbonization based on credible and flexible chain of custody practice. This Part I explores the common ways a “Mass Balance” chain of custody model is used in the transportation value chain—and its associated emissions reporting. Part II explores “Book and Claim” and how to “B.Y.O.” (bring-your-own) SAF and apply its profile to your logistics supply chain and reporting.

In order to jumpstart voluntary investment in transportation decarbonization, experts have encouraged enabling a “market-based” approach to low emission transportation procurement and corresponding accounting and reporting (see our blog on advocating for credible flexibility). In addition to regulatory measures, the market is capable of supporting “voluntary” measures that encourage greater supply of low emission fuel solutions and services. Demand is growing, supply is lagging, and many agree that such a flexible, market-enabling approach is necessary to kickstart the market.

Despite enthusiasm, the transportation sector is highly complex, and basic accounting and reporting practice quality does need to improve in order to make this vision a reality. This helps attributes and claims balance within any market-based system, be considered “similar in nature”, and remain credible. Tracking and tracing the exact physical emissions associated with one voyage, one movement of cargo, on one specific quantity of fuel has always been a herculean task (think of a vessel with hundreds of cargo owners, multiple fueling events, on a multi-port, multi-month voyage).

Methodologies like the GLEC Framework and the transportation sector’s emissions accounting standard ISO 14083 provide as close as possible to a scientific method to account for and allocate physical emissions across the transportation supply chain. However, realities of the transportation ecosystem have all but demanded flexibility since these standards were originally developed. Part of the issue was a lack of language and rules. Enter SFC’s Voluntary Market Based Measures Framework for Logistics Emissions Accounting & Reporting (MBM Framework), which leverages standard chain of custody methodology and provides language for MBM practices.

Not only is it hard to track and trace physical emissions, such rigidity may actually hinder investment in green fuels and low emission cargo services. In simple terms, cargo owners (i.e. the customers of a transport service) are more likely to invest in a low emission transportation service if they are able to receive the full benefit of their procurement investment rather than share it with everyone else on the vessel who did not pay for the green premium.

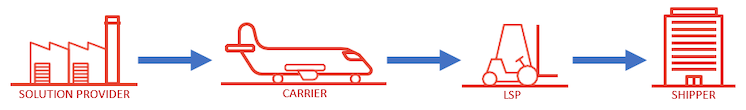

The limitations of a purely physical approach are surmounted, in part, by utilizing proven “chain of custody” approaches already used in-sector today, predominantly: mass balance and book and claim. Think of a chain of custody model as the “handshakes” between organizations as physical goods—plus data and attributes—move through a system. Despite innumerable potential combinations, we can summarize the principal chain of custody applications present in market-based transportation practices. Attention to these models helps all parties better understand and employ market-based measures (MBM) ensuring efforts enhance existing emissions accounting rather than distract from practices that have been honed over the last decade. Even via MBM, users still need ground truth. Perhaps, especially so. Good practices, industry-wide, enable accurate and secure claims, prevent double counting, and ultimately increase sector decarbonization.

We invite you to explore the two (2) places where “mass balance” is used in the transportation decarbonization ecosystem in Part I. In Part II, we explore the three (3) places where “book and claim” is employed and how an organization can best “B.Y.O.” (bring-your-own) fuel and still account for the lower emissions profile following as-close-to-standard convention as possible. (Note: with BYO, we refer to the practice of a cargo owner/organizer procuring the lower emission profile of a fuel straight from a fuel provider rather than a service attribute from a carrier)

Mass Balance

As discussed above, a chain of custody model transfers, monitors and controls inputs and outputs in a supply chain (see ISO 22095). Mass balance is used in a variety of industries to mix products or services and track of the inputs and outputs. If you’re reading this to learn primarily about “book and claim”, hold that thought for Part II, but also consider how the two models may co-exist in the same supply chain. The two places in the standard transportation supply chain where a “mass balance” chain of custody is used are both key building blocks to understanding and applying a book and claim chain of custody in transportation, too.

For today’s purpose, we’ll include the full definition of mass balance from the ISO 22095:

- Mass Balance: chain of custody model in which materials or products with a set of specified characteristics are mixed according to defined criteria with materials or products without that set of characteristics.

- Note 1: The proportion of the input with specified characteristics might only match the initial proportions on average and will typically vary across different outputs.

Said another way, inputs will be mixed, and a user may receive an actual physical thing (e.g., a fuel or a transportation service) and a related administrative record that may vary. At the system level, all inputs and outputs are in balance. In transportation, the claimant’s procured emissions profile is the “thing” that makes it to their inventory. Now, let’s explore two prevalent places this model is used in the transportation supply chain.

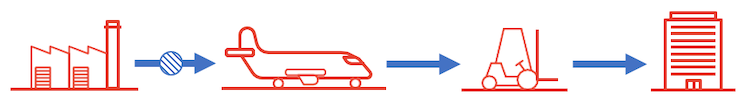

Fueling disproportionately

Bringing fuel to market depends on a highly-complex chain of custody in the common sense of the term: an amount of “stuff” passing hand-to-hand until its destination, a fuel tank, where it’s burned to provide transportation services. Think of pipelines, fuel trucks, and fuel depots at a transportation hub. In order to cost-effectively bring low emission fuel to market, the sector depends on blending and mixing compatible fuels. Who wants to delay decarbonization only to build a dedicated pipeline or obligate separate tanks[PP1] if we can blend diesel and biodiesel or if we can safely mix SAF and Jet A-1 for delivery to airports? Enter mass balance and our first application: fuel delivery.

Let’s imagine a 100-liter fuel depot sitting at a maritime port that already contains 99 liters of fossil diesel. When we input 1 liter of 100% biodiesel, we now have a tank that is a 1% biodiesel blend after mixing. In theory, anyone who physically fuels one liter from this tank will physically receive 1 part B100 and 99 parts fossil diesel.

However, rather than follow a strict, physical-only logic, the intention of mass balance is to allow for the disproportionate allocation of the inputs and the outputs. Returning to that full, 100-liter tank of blended 1% diesel. The rules of mass balance allow the operator to allocate the administrative record of the original 1 liter of pure 100% biodiesel to a single vessel (even though we recognize the physical fuel itself reflects the 1-part/99-part nature described above). To keep the system in balance when designating this pure, single liter of B100 to one claimant, all subsequent vessels would receive an administrative record of 100% fossil diesel. The fuel depot operator knows what each group receives, and its operators likely know that they are receiving some of the biodiesel as well (e.g., similar to a consumer-level fuel station where it advertises: “up to a B# blend” ).

A few key concepts help the fuel depot admin manage the fuel mix and its administrative record-keeping. There is a method to the fuel data tracking and tracing as it enters the depot. While there are variations in mass balance system design, these concepts should be well-defined by the operator(s):

- Physical system boundary: In the above example, it’s the 100-liter fuel depot. The boundary is defined by the system owner or scheme owner and is thus, semi-flexible but must be defined when put into practice. It could be a single pipeline or may be a connected fuel network.

- Balancing period: The fuel depot operator tracks numbers and units over time in a defined manner to ensure inputs and outputs—and their administrative records—are appropriately related and balanced.

- Physical presence—the likelihood of the input being present in the output (this is quite obvious in a single 100-liter tank, less so in a large methane gas pipeline when one considers complex mixing properties of gases, for example).

Mass balance isn’t magic. It’s a system and demands rigor so that it can enable the industry to take real, traceable steps to decarbonize their supply chains.

Zoom out. Our vessel operator fuels one liter of physically-mixed biodiesel, receives its administrative record as a pure liter of B100 via mass balance, and sets sail for its destination—with tens of different cargo customers aboard—and considers the next place where it may employ a mass balance chain of custody: the transportation service!

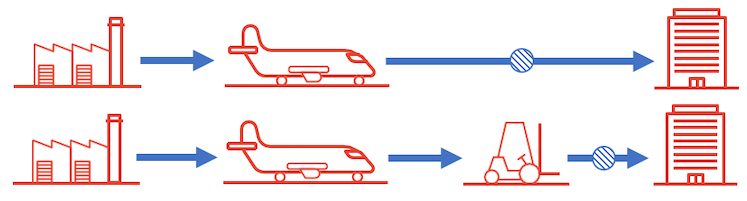

The "Disproportionate" Transportation Service

Now that we have seen how the sector leverages the flexible and physical approach within the fueling stage, we look at mass balance in a transportation service. The carrier may have goods from many cargo owners on its vessel, and at the end of the day, multiple destinations along its voyage from A to B to C to D. The sustainability challenge today is that, among its many cargo owners, only one client may be willing to pay the “green premium” that allows the carrier to purchase any biodiesel at all from the afore-mentioned fuel depot.

Carriers purchase fuels to generate transportation services. Cargo owners purchase these services. In order to enable their client to purchase the low emission transportation service, the carrier can utilize the same logic of mass balance with fuels to disproportionately allocate inputs and outputs of services among its physically-connected clients. Within this transport chain between origin A and destination D, it has tracked the mass of its consignments, distances traveled, and calculates the total transportation activity (e.g., tonne-kilometer, generally, or TEU-km for maritime—see “Q&A” with an SFC team member). It then calculates associated emissions, following the GLEC Framework guidance and ISO 14083 standard, and reports a selection of data to its stakeholders (e.g., kg CO2e/tonne-km and other data of the low emission transportation).

In a balanced system, the 1 liter of biodiesel is integrated into the voyage’s reporting. Under a strictly physical attribution, all clients will receive some “piece” of this fuel. Under a market-based approach taken with regard to the transportation service, the carrier may disproportionately allocate the low emission transportation service attributes that were created by this biodiesel to one cargo owner. The carrier is balancing the inputs and outputs of sustainable transport services within its system and will be using an appropriate tool to track these data.

Note: One liter of biodiesel is a simplification. In reality, a vessel will have many thousands of liters or kg of fuel implicated, millions of tkm, and the operator will likely be tracking fuel, cargo mass, distance traveled, and emissions at the level of the trade lane or transportation operation category, TOC—see “Addressing Misconceptions in Emissions Accounting” for more on reporting and TOCs).

The same concepts apply to services that as to fuels above: system boundary, balancing (time) period, and physical presence. Was the service delivered in the same system boundary? Within the system’s time rules? Was there a chance the cargo owner’s consignment could have been connected to this biodiesel-enabled service? If we follow the maritime vessel example above, piloting around the mediterranean between A-B-C-D ports along with other vessels as part of a fleet, the mass balance boundary, time period, and mixing is quite apparent. If the carrier has regional blocs of service territories across the world, despite its global presence, it will likely not disproportionately allocate from the Mediterranean to a customer only connected to a bloc of operations in the Gulf of Mexico, for example.

Generally, the mass balance chain of custody for services is employed where many cargo stakeholders share the same transport where low emission fuel is deployed or where a fleet has consistent transportation routes. Another example is a trucking route of one or many trucks between warehouses. The system is one big, regular circuit! The carrier fuels with a low emission solution anywhere in this circuit to satisfy one of its cargo owners’ requests for a low emission service. Rather than need to adjust operations heroically to ensure the biodiesel- or electric-fueled truck physically matches exactly with the paying cargo owner’s consignment—potentially implicating greater emissions and cost—the request is satisfied employing a mass balance chain of custody. (Repeat recommendation: utilize TOCs).

Mass Balance Summary

In summary, physically-connected systems for both fuels and services may be disproportionately procured and reported via a mass balance chain of custody, provided necessary rigor and system inputs always equal outputs. It is possible to follow GLEC and ISO 14083 in a mass balance-based system. This flexible chain of custody already underpins much of how we fuel, purchase, load cargo, and—of course—account for the sustainable attributes of these fuels and services in B2B reporting and a corporate emissions inventory.

Disproportionate allocation via mass balance is one of the methods referred to with “market based measures” in the SFC MBM Framework. In Part II, we review the (3) places the “book and claim” chain of custody model is used in the market-based transportation supply chain and how to allocate and report associated emissions.

Read the full Part II blog in this Chain of Custody series here.

Verification Note: See the MBM Specification section 6.3.1b for the four conventions that SFC asks Emission Reporters to document when reporting under “mass balance” chain of custody models.

For more on the SFC MBM Verification program for reporting find the Assurance program here.

For more information: MBM Homepage or e-mail MBM@smartfreightcentre.org to sign up for communications regarding program updates.