PART II—The Three Ways You “Book and Claim” in Market-based Transportation Emissions Accounting and Reporting

This is Part II of a series exploring a “market-based” accounting and reporting approach to transportation decarbonization based on credible and flexible chain of custody practice. Part I explored application of the “Mass Balance” model. This Part II explores the common ways a “Book and Claim” chain of custody model is used into the transportation value chain and its associated emissions reporting.

In order to jumpstart voluntary investment in transportation decarbonization, experts have encouraged enabling a “market-based” approach to low emission transportation procurement and corresponding accounting and reporting (see SFC 2023 blog advocating for credible flexibility). In addition to regulatory measures, the market is capable of supporting “voluntary” measures that encourage greater supply of low emission fuel solutions and services. Demand is growing, supply is lagging, and many agree that such a flexible, market-enabling approach is necessary to kickstart the market.

Despite enthusiasm, the transportation sector is highly complex, and basic accounting and reporting practice quality does need to improve in order to make this vision a reality. This helps attributes and claims balance within any market-based system, be considered “similar in nature”, and remain credible. Tracking and tracing the exact physical emissions associated with one voyage, one movement of cargo, on one specific quantity of fuel has always been a herculean task (think of a vessel with hundreds of cargo owners, multiple fueling events, on a multi-port, multi-month voyage).

Methodologies like the GLEC Framework and the transportation sector’s emissions accounting standard ISO 14083 provide as close as possible to a scientific method to account for and allocate physical emissions across the transportation supply chain. However, realities of the transportation ecosystem have all but demanded flexibility since these standards were originally developed. Part of the issue was a lack of language and rules. Enter SFC’s Voluntary Market Based Measures Framework for Logistics Emissions Accounting & Reporting (MBM Framework), which leverages standard chain of custody methodology and provides language for MBM practices.

Not only is it hard to track and trace physical emissions, such rigidity may actually hinder investment in green fuels and low emission cargo services. In simple terms, cargo owners (i.e. the customers of a transport service) are more likely to invest in a low emission transportation service if they are able to receive the full benefit of their procurement investment rather than share it with everyone else on the vessel who did not pay for the green premium.

The limitations of a purely physical approach are surmounted, in part, by utilizing proven “chain of custody” approaches already used in-sector today, predominantly: mass balance and book and claim. Think of a chain of custody model as the “handshakes” between organizations as physical goods—plus data and attributes—move through a system. Despite innumerable potential combinations, we can summarize the principal chain of custody applications present in market-based transportation practices. Attention to these models helps all parties better understand and employ market-based measures (MBM) ensuring efforts enhance existing emissions accounting rather than distract from practices that have been honed over the last decade. Even via MBM, users still need ground truth. Perhaps, especially so. Good practices, industry-wide, enable accurate and secure claims, prevent double counting, and ultimately increase sector decarbonization.

In Part I, we explored the two (2) places where “mass balance” is used in the transportation decarbonization ecosystem. These systems are building blocks for the market-based approach in transportation and are often combined with the use of a book and claim chain of custody systems in market-based transportation practice.

In this Part II, we explore the three (3) places where “book and claim” is employed and how an organization can best “B.Y.O.” (bring-your-own) fuel and still account for the lower emissions profile following as-close-to-standard convention as possible. (Note: with BYO, we refer to the practice of a cargo owner/organizer procuring the lower emission profile of a fuel straight from a fuel provider rather than a service attribute from a carrier)

Book and Claim

The term “book and claim” is an established chain of custody model that has recently reached somewhat of a buzzword status. However, this buzzword holds big promise for sustainable transport—the humble yet powerful potential to connect supply and demand. Investing in book and claim-enabled decarbonization is often confused with “offsets”, and its good application by transportation stakeholders can help the industry unlock much-needed key decarbonization investment. This potential is thanks to the application of credible administrative record-tracking strategies in book and claim systems that maintain connection and traceability to a physical good or service despite physical (i.e., geographical) disconnection from the record itself.

A book and claim model can enable that supply of sustainable inputs (e.g., oilseed feedstocks) be turned into sustainable fuel locally, injected into a nearby fuel depot or facility (e.g., an airport), and its quality of being low-emission can be administratively connected to the global supply chain instead of being physically shipped across the world. Supply doesn’t need to unnecessarily chase physical demand. The model enables shorter supply chains where physical fuels may connect to their nearest airport instead of a costly and emissions-intense global distribution network. When a willing buyer cannot physically connect to the supply of a sustainable fuel or a low emission service, how can they still invest, support market development, and make robust claims to the lower emission profile of a sustainable fuel or service? Enter book and claim-based MBM.

Like in Part I, let’s return to basics with the ISO 22095 definition of “book and claim” and its two notes:

Book and Claim: chain of custody model in which the administrative record flow is not necessarily connected to the physical flow of material or product throughout the supply chain.

- Note 1: This chain of custody model is also referred to as "certificate trading model" or "credit trading".

- Note 2: This is often used where the certified/specified material cannot, or only with difficulty, be kept separate from the non-certified/specified material, such as green credits in an electricity supply.

Despite the use of the term “credit” in the definition, we note that the ISO committee wrote this definition for all industries, definitely not just transportation. Think: grain, plastic, chemicals, etc. ISO is in the process of updating the book and claim standard and will use more-precise wording which may help avoid one issue: the term “credit” can be a root of common misconceptions about book and claim’s relation to “carbon offset credits”. Here the word “credit” simply refers to tracking of inputs and outputs, similar to the logic of a mass balance system (+1 shall be balanced by a -1). (Example of credit confusion: response to SBTi news from April 2024)

A book and claim-based system, then, enables inputs and outputs to be tracked independently of their physical embodiment. A fuel may be physically delivered in Tokyo, and the administrative record flow of its attributes (e.g., the lower emissions intensity) may be claimed in Miami. No vessel is needed to physically transfer the physical fuel across the world.

Furthermore, in similar fashion to the exploration of mass balance in Part I, book and claim can be applied to products (e.g., fuels) and services (e.g., transportation of cargo). The examples below follow a similar path to the two mass balance chain of custody examples, and we explore one more “straight to consumer” use case that deserves special attention given the novelty of the physical disconnection allowed under a book and claim model.

Fueling via Book and Claim

When we’re in Tokyo and have a fuel farm at an airport, be it 100 liters or 100,000, it could be operated under a mass balance chain of custody as detailed in Part I, allowing mixing of compatible fuels, but it also might follow a book and claim chain of custody. Why? As noted, the actual buyers seeking “low emission” aviation fuel might not have a physical connection to the Tokyo International Airport.

Whether in Miami, Sydney, or Mexico City, it is likely preposterous for an air carrier to fly out of its way to pick up the SAF from Tokyo, and the low emission fuel may remain unpurchased. Like any product sitting on a shelf, if the seller is unable to connect its supply to demand, the fuel farm operator in Tokyo will not receive the market signal to purchase more of this product. With a low demand signal, the existing production facility doesn’t receive its own signal to ramp up SAF production or graduate from co-processing.

Under a book and claim chain of custody, the fuel farm operator and/or fuel producer can go beyond disproportionate allocation within the pool of physically-connected carriers (i.e., mass balance) and expand its potential buyers. It can allocate the administrative record of the SAF to an air carrier in Mexico City, provided it balances inputs and outputs within the system boundary. The airplane in Mexico City effectively flies on a SAF emission profile while the Tokyo supplier ensures the emissions profile of the actual, physical fuel delivered in Tokyo is reported as the residual mix—in this case, fossil jet fuel. The fuel emission profiles effectively swap places.

There are other details that make this intercontinental, non-physical administrative record flow possible. For one, it is encouraged for the parties involved to use credible registries to reduce the chance of double counting and prevent other issues that may put the distant carrier’s claim to the SAF fuel volume in jeopardy of “double counting” (see the Book and Claim Community’s P&BP publication for some agreed-upon concepts). In similar pursuit of greater integrity, it’s highly recommended that all parties have end-to-end, verified emission reporting—best if verified to ISO 14083, the transportation standard.

Similar to mass balance, the point is not to add complexity but to enable, first, clear claims and second, greater uptake of sustainable fuels. Additionally, similar to mass balance, there are key concepts that help govern the book and claim model application in time and space to ensure high quality claims: vintage, double-counting prevention, additionality, and similarity in transportation accounting (note: these also reflect the SFC MBM Framework’s integrity measures).

Note: Reminder from the definition that a book and claim “system” means attributes may be administratively separated from their supply. Within the system, it may also be physically-connected (e.g., RECs or GOs). The “both/and” logic creates simplicity for all system users (certificates, tracking, etc.) and allows for more physically-connected options to exist within the system as well.

The goal, when leveraging a book and claim model, is to enable greater use of sustainable fuels and signal to the nascent “solution” (e.g., fuel) market that we need more! The goal is also to enable carriers to generate low emission transportation services and for all parties to enjoy a clear claim to the lower emission profile.

In our example, the airline selects its SAF attribute from a registry, traced to physical SAF in Tokyo, and procures it in order to generate a low emission service. This is the next place in the transportation value chain where book and claim is employed—the transportation service.

The "Booked or Claimed" Transportation Service

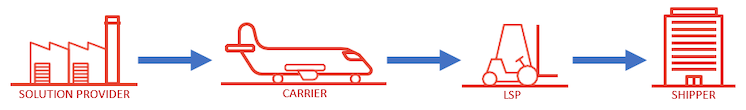

An air carrier books and claims by purchasing the same “thing” it normally buys: fuel, albeit from a physically-disconnected source, enabled by a book and claim-based administrative record flow. Now, let’s look at how downstream organizations such as cargo owners and logistics service providers (LSPs) can also secure the “thing” that they normally procure, enabled by a book and claim chain of custody: the transportation service.

The LSP and the shipper don’t own vehicles and do not conduct transportation activity themselves. As such, they are not direct purchasers of fuels. However, LSPs do organize transportation services, and shippers do own goods that need transportation services. Both organization types are key for providing the demand signal for low emission services—via any chain of custody model. As such, in book and claim procurement, the low emission transportation service is the most “similar in nature” option for LSPs and shippers to pursue.

As we saw with mass balance in Part I, the carrier may have goods from many cargo owners on its vessel, and some organizations may not wish to pay for a low emission transportation service. If the carrier is at a port of call where a low emission fuel is available, they will not be incentivized to voluntarily purchase this fuel unless their clients wish to procure a low emission service. Swapping perspectives, the LSP or the shipper may wish to purchase a low emission transportation service, willing to cover the green premium, but their carriers may not be able to access the fuel and thus cannot physically provide the service offering. Enter book and claim for transportation services.

The procurement of the transportation “service” via a book and claim chain of custody may occur in one of two places. In both cases, it is the carrier who is conducting the actual low emission transportation service—burning the fuel in its assets—which is passed or booked down the value chain.

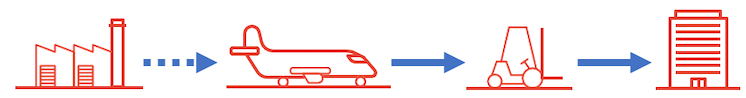

First, the physical disconnection may happen after the carrier and before the LSP or shipper. As such, the LSP procures the attributes of a low emission transportation service from a carrier where it has no physical goods being transported (the physical disconnection). For example, the LSP wants eTrucking services for downstream clients, but its carrier network doesn’t generate such services. The LSP sources the attributes of such a service from a disconnected carrier who does offer eTrucking services. The LSP applies this profile to its own fossil trucking services that it has organized on behalf of its client. Physical would likely be easier if it were available, but when it is not available, the LSP overcomes this barrier with the book and claim system.

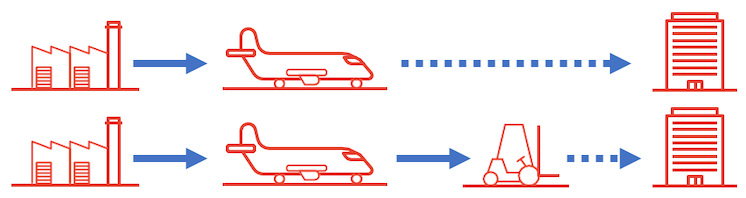

To reflect supply chains where there is no LSP intermediary—where the shipper works directly with carriers—the shipper may also procure the physically-separated attributes of the transportation services straight from a carrier. The physical disconnection is at the carrier-shipper relationship. Their physical cargo is not actually transported on the carrier’s low emission-powered assets, but they procure the attributes of the low emission service and report as if it had been.

In the second “place”, the physical disconnection may occur between the LSP and the shipper. In this case, the LSP sources low emission transport within its network of carriers and provides this service to a shipper which is not physically connected to the LSP’s freight forwarding activities. The shipper’s physical cargo is not actually transported within this LSP’s network of carriers, but they procure the attributes of the transportation service and apply it to their inventory as if it had been.

Lastly, we note that book and claim of services may be employed by combining chain of custody methods, including at the fueling and service stages. When you consider a transportation chain involving a fuel provider, a carrier, an LSP, and the cargo owner… there are many combinations!

These “places” where one finds book and claim (or mass balance) are the building blocks of the market-based transportation supply chain.

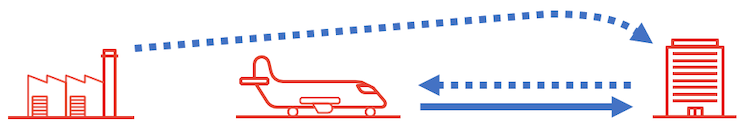

Shipper secures Low Emission Attributes from a Fuel Provider

Finally, one popular early procurement channel for pioneering shippers has been for a shipper to leverage the book and claim chain of custody approach to procure the attributes of sustainable fuels straight from a fuel producer! In this case, the shipper is solving an extreme problem: its suppliers are not offering the low emission transportation services that it needs. The shipper wants to meet its own targets and support the greater uptake and development of sustainable alternatives to fossil fuel but also very much needs to be able to claim the lower emission transportation in its own inventory.

In this modality, the shipper is doing something that it normally doesn’t do—purchasing fuel. In reality it’s purchasing the attributes of the fuel, but the idea is the same. It seeks to apply this profile to its own transportation as if it had procured actual services conducted with said fuel. The shipper secures its own future, and it’s understandable why. Commitments to its clients—or perhaps due to an SBTi target—are very real and inspire this actor to search outside of its physical network to satisfy its demand.

The disconnection of the administrative flow from the physical product in this case is unique. The fuel attribute is passing from the fuel producer to the cargo owner, and it should still include a strong tie to an air carrier to be consistent with applicable accounting standards and to ensure the scopes are appropriately correlated. In early procurement of this style, the attribute flow often “skipped” over and was invisible to any carrier or LSP. Scope 1 wasn’t counted by anyone. More recent practice is to ensure there is a scope 1 and scope 3 claimant and the users may allocate this profile physical transportation between the shipper and a partner carrier.

This procurement model is compelling yet often requires some extra work to set up. On the one side, the demand signal for sustainable fuels could not be more clear—the shipper is stepping up and taking the responsibility to procure what it wants to see in the market. On the other hand, the shipper assumes the responsibility of applying this emission profile in its inventory in a high quality manner, as close as possible to the scenario where its providers had actually used the low emission fuel volume. Difficulty level = high, and this approach requires particular double counting risk mitigation.

Like bringing your own bottle of wine to a restaurant, it is as if the Shipper bought its own fuel and handed it to their transportation service operators for their use. One difference to this restaurant bottle analogy in practice is that such direct-to-shipper attribute procurements are often pursued after the shipper’s cargo has already been transported, often towards the end of the year and backward-applied to the year’s transportation via a “reporting year allocation” (see SFC interpretation #4). The shipper reports as if its cargo had been transported with this low emission fuel earlier in the year.

Without early shipper demand of this variety, we may not be talking about book and claim as a decarbonization tool. Much like the energy sector, early buyers laid the path upon which we tread today. Systems were built around early renewable electricity purchases that made future buyers of environmental attribute certificates (EACs) look closer and closer to real power purchases.

The shipper’s application of these emission profiles in their inventories seek to mirror the traditional supply chain. This takes expertise, though some of them make it look so easy that it’s worth taking a minute to describe how other shippers, attracted to the seeming simplicity of this approach, can also “B.Y.O.” (bring-you-own) fuel and still make a high-integrity claim in B2B and year-end emission reporting.

Report on Fuel Profiles like a Pro—Even when you B.Y.O. (Bring Your Own) Fuel

One key challenge the shipper assumes when choosing to “B.Y.O.” SAF lies in establishing accurate accounting mechanisms for SAF volumes first in their own physical inventory, across both regulatory and voluntary markets, and in their market-based accounting. Ensuring that SAF quantities are properly reported in carbon balance sheets requires alignment and a strong internal standard operating procedure to mitigate erroneous double-counting risk, to define additionality measures, and ensure high-quality claims with upstream and downstream partners.

To ensure accurate and secure SAF integration into accounting systems when taking this approach, these simple steps should be followed by Scope 1 (carriers) and Scope 3 reporting companies:

Step 1

Identify a transport service based on the mode of transport, vehicle type, its fuel needs, and the corresponding transport activity performed.

Step 2

Calculate emissions using the fossil emission factor for kerosene and the emission intensity, relating absolute emissions to the transport activity in tonne-kilometers (tkm).

Step 3

Create a Low Emission Transport Service (LETS) by implementing a low emission solution—here, SAF. It is crucial to understand the reduction potential of SAF compared to conventional kerosene and the corresponding emission factor of such.

Step 4

Calculate the absolute emissions based on the fuel needs identified in Step 1 and the replacement of kerosene with SAF. Relate the emissions again to the performed transport activity to determine the new emission intensity of the LETS.

Step 5

The new absolute and relative emissions are compared to the baseline to determine the delta. The lower emission profile from the LETS can then be included in the overall carbon accounting of the company reporting in Scope 3. The attribute of the transportation had the service been fossil kerosene if the "reference case" that is provided to non-participants of the decarbonized transport (the LETS).

Intentional accounting, together with clear guidance and quality controls, are required to ensure high quality transportation claims and to ensure that both absolute and relative emissions claims from fuel substitution are accurately reflected—especially when claimed by multiple Scope 3 stakeholders across the value chain.

For more chain of custody reading, Part I on common application of Mass Balance, is here.

For more MBM programming details, please visit the MBM Homepage or email the program team: MBM@smartfreightcentre.org